by crissly | Apr 25, 2023 | Uncategorized

That ban helped set the path for the development of the Chinese metaverse, experts say, since it decoupled virtual spaces from digital assets. “The key difference [in the metaverse] between China and the rest of the world is it’d be heavily regulated in a centralized manner,” says Zhengyuan Bo, a partner at China-focused research firm Plenum. “And there’s only limited space for growth without [digital assets] for monetization.”

It isn’t just crypto that the government has cracked down on. Gaming—which has formed a pillar of the metaverse in the West—has also come under pressure from the top. Amid fears that young people were becoming addicted to online games, state media dubbed the industry “spiritual opium.” Between 2018 and 2022, the government froze the issuance of licenses for new games for 17 months in total and, in 2021, limited minors to three hours of gaming time per week.

But the government is willing to back pieces of the metaverse that it feels could be directly beneficial to the economy. Digital twins were included in Beijing’s 14th Five Year plan, the enormous economic strategy document that sets the national agenda from 2021 to 2025. An action plan published late last year by five ministries, including the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, promised to grow the virtual reality industry to 350 billion yuan ($51 billion).

The high-level plan identified innovations they’d like to see more of, including near-eye display (a way to project images onto a user’s eye); rendering processing (turning 2D or 3D models into realistic images), sensory interaction, and network transition.

But support from the government is conditional—Beijing has a vision for what metaverse tech is going to do for China. That means, instead of a virtual world where people can socialize, work, and play, the metaverse needs to serve China’s physical economy.

“At the current stage, everyone emphasizes industrial applications from education, medical, travel and industrial development,” says Siri Chen, HiAR’s marketing director, speaking from the company’s headquarters in Shanghai’s Zhangjiang Hi-Tech Park. In a demo for WIRED, a HiAR employee acted as a factory worker in a HiAR headset and was remotely asked to fix a valve.

Other metaverse-related companies have pivoted in anticipation of investment from the government. For Eric Liu, cofounder and CTO of Shanghai-based digital twin company Digitwin Technologies, the 14th Five Year Plan has helped underpin his company’s shift to focus on energy and manufacturing—“a field that previously wasn’t ready” for this kind of tech, he says.

While the Chinese government’s desire to shape the metaverse may limit its scope, state support may mean it doesn’t fall victim to the notoriously fickle tech sector, which moves on from trends at great speed. Startups often try to be “in the middle of a whirlwind,” meaning the right trend with an explosive growth potential.

“If anything gets buzzy in China, you see companies swarm into the space,” says Jingshu Chen, cofounder of VR company VeeR. “However, if growth isn’t as fast as their expectation, more companies are also likely to pivot.”

by crissly | Apr 25, 2023 | Uncategorized

For almost two decades after it opened in 1913, Michigan’s Central Station was a major stop on the nation’s interurban rail network. Then the private car took over the US, and Detroit declined. By the 1970’s, white residents were fleeing to the suburbs, auto jobs were leaving the state and the country, and local corruption soared. At the turn of the century, the train depot and the 18-story office towers behind it had been abandoned for 30 years, the faded exterior looming over Detroit’s Corktown and Mexicantown neighborhoods, a sign that things were going very poorly in Detroit.

By 2018, the city and Ford Motor Company were ready to tell another story. That year, Ford announced that it had acquired the station and the area surrounding it, a monument to the kind of transportation past that the automaker and its manufacturing brethren had all but killed.

Today, Ford executives and city government and community leaders will hold an opening ceremony for one building on the station’s new campus, part of a $950 million project it is calling Michigan Central. (The state of Michigan contributed some additional $126 million in new and existing financing to the project.) The new building, called the Book Depository, will serve as an innovation collaboration space for transportation entrepreneurs and researchers.

Bill Ford, executive chairman of Ford says the campus’ redevelopment is a sign. “Michigan Central will go from being a story about Detroit’s decay to the story about Detroit’s rebirth,” he says, a second act that will see the city become home to tech- and auto-centric jobs that will build the next generation of transport. “This will be the first tangible evidence that that vision is coming to life,” says Ford, who is also a great-grandson of both company founder Henry Ford and tire magnate Harvey Firestone.

Ford is part of a broader movement to revitalize downtown Detroit, though its effects are not yet clear. Detroit lost almost half of its population between 1950 and 2000. Though new downtown sports stadiums, restaurants, and housing developments have strengthened the case of local optimists who see a resurgence underway, recent US censuses suggest that the region continued to bleed residents in the past decade, perhaps due in part to the Covid-19 pandemic. (The city has sued the US Census Bureau over the results, alleging the feds undercounted minority residents, which affects government funding.)

Ford expects many other businesses to move onto the 30-acre Michigan Central campus, which also includes 14 acres of park space open to the public. Today’s opening focuses on the Book Depository, a nearly 100-year-old building across the street from the Central Station that once played host to the Detroit public schools’ store of books, records, and supplies. Now, it will serve as a 270,000-square foot maker and startup space focused on mobility, a potential spawning ground for future Ford partners. Even before the building’s official opening today, more than 25 companies representing 150 employees have taken up residence at the Book Depository, Michigan Central officials say, representing firms working on autonomous and electric vehicles, roadways built just for robot cars, and air pollution. They are all associated with an organization called Newlab, a manufacturing incubator that has already launched an innovation space in Brooklyn’s Navy Yard.

by crissly | Apr 18, 2023 | Uncategorized

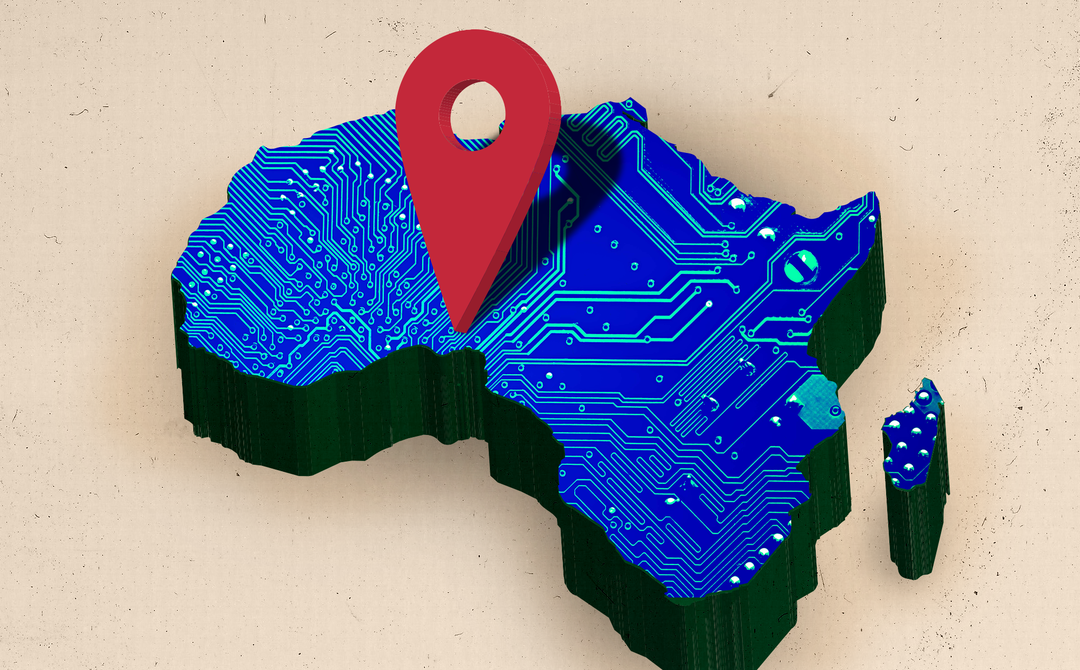

Asked to comment on the plans, Binance’s West & East Africa director Nadeem Anjarwalla said in a statement: “As we continue to support blockchain adoption across the African continent, Binance is keen to collaborate with the Nigeria Export Processing Zones Authority [the regulator overseeing the Lekki Free Zone] to establish a virtual free zone with the aim of generating long-term economic growth through digital innovation. We look forward to sharing key details when plans have been finalized.”

That a Nigerian government agency signed off on a crypto partnership at all is surprising. While Nigeria is one of the world’s biggest global marketplaces for crypto, ranking 11th overall in crypto research firm Chainalysis’ Global Crypto Adoption Index Top 20 in 2022, the country’s regulators have often been hostile. The Central Bank of Nigeria banned banks from enabling cryptocurrency transactions in February 2021.

Adesoji Adesugba, CEO of the Nigeria Export Processing Zones Authority, said in a statement that the partnership with Binance seeks to “engender flourishing Virtual Free Zones to take advantage of a near trillion-dollar virtual economy in blockchains and digital economy.”

“It’s clear that the world is going crypto,” says Edu. “And Nigeria can’t lock that door forever.” Incoming president Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s manifesto appears to echo this, saying that his administration will “reform government policy to encourage the prudent use of blockchain technology.”

While developing its digital infrastructure is Itana’s main preoccupation right now, building the physical city might not be simple, judging from the experience of nearby development projects. Eko Atlantic, a private city project built on sand “recovered” from the ocean outside of Lagos, has made faltering progress since 2009.

The Lekki Free Zone has itself been trailed by controversies over the alleged displacement of local communities to make way for the project. Local residents say more than a dozen villages in the Ibeju-Epe area, where the free trade zone was established, have been unilaterally reclaimed by the government, some to make way for a not-yet-operational oil refinery which started construction in 2016.

“They said they wanted to use the land for revenue purposes, that there was no refinery in Lagos state, so they were planning for our children,” Otunba Ladipo Olusanya Adeokun, a community leader of the Idashon Community in Ibeju Lekki, says. “What about us who will bear the children, are we not going to plan for our future? Where’s the money we are going to use to take care of our children?”

Communities around the free port area have limited access to power, while Lagos itself suffers from a crippling housing shortage. Building a new, high-end community like Itana isn’t likely to solve those problems in the near term.

“What I can tell is that it’s not going to be cheap,” says Yakubu Aliyu Bununu, lecturer in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning at Ahmadu Bello University, Nigeria.“If you look at the purchasing power of an average Nigerian, it’s going to take them years and years to be able to earn an income that would allow them to live in Eko Atlantic, or Alaro City, or any of the cities springing up in that area,” says Adunbi. (Alaro City, where Itana is due to be located, advertises residences priced from $65,950; the average yearly income for Nigerians was $2,080 in 2021.)

But Aboyeji says Itana’s goal isn’t to cloister the affluent in air-conditioned high-rises. “We’re not just trying to get together a bunch of opulent, rich people into a space, right? What we’re trying to do is pull together a productive young population.”

Right now, the 72,000-square-meter plot of land that will be Itana sits empty. What was once a swamp has now been filled in with orange sand, waiting for the first foundations to be laid. But, as Aboyeji insists, the project is all about potential, about being a vessel for the restless ambition of Nigeria’s tech scene.

“We’re not some foreigners that are trying to conquer Nigeria. We are Nigerians trying to figure out, within Nigeria, a place where we can operate our businesses and build for the world,” he says. “I think we will be giving a lot of lessons to the West on that.”

by crissly | Apr 12, 2023 | Uncategorized

“After Covid, [cab-hailing platforms] don’t have any management. They have fired many employees. There aren’t many staffers to help out [drivers on ground]. Who do we take these issues to?” Matthew says. “At least before, there was a concerned office [to address disputes], now there is no concerned office. Everything is online.”

Ola did not respond to questions sent by WIRED.

Rathi from CIS says that a responsive grievance mechanism for gig workers is “completely absent” and continues to be “one of the top three demands” that workers have. “The firms are able to provide more responsive services to customers,” he says. “The workers are as important if not more [than customers], and they should be able to extend the same kind of mechanisms, practices, and policies to workers.”

Because workers are often in precarious economic situations and have no jobs to fall back on, being mugged or attacked has a huge impact on their ability to earn.

Some of the platforms do offer limited insurance for gig workers, including for accidents. However, these don’t necessarily provide much respite, according to Aditi Surie, a senior consultant at the Indian Institute for Human Settlements, a research organization based in Bangalore, who has studied the schemes. Her research showed that making a claim against the platform-provided insurance is a long and laborious process. “So even if you have grievous bodily harm, there are lots of steps that prevent anyone from making use of any insurance or offering from the platform,” Surie says. “So, if you’re in a road accident, for example, the police have to get involved. Now finding the right police station, contacting your insurance in time, getting the ambulance there—these are all things that platforms say they try and help with but there is nothing there—which again then falls back on the worker.”

Uber spokesperson Tomar says that the company gave Devi financial support to cover her loss of earnings as a result of the incident, and that the company “helped her claim her medical expenses under Uber’s on-trip insurance policy, which covers all drivers on the app.” Devi claims that both the insurance money and Uber’s financial support for her loss of earnings haven’t made it into her bank account.

“Uber is deeply committed to the safety of drivers on the Uber app,” Tomar says. “Uber drivers have many of the same transparency and accountability features that riders do, such as feedback and ratings for every trip, GPS tracking, an emergency button, and shared trip feature.”

In Delhi, Devi has had enough of Uber, which she says isn’t safe or profitable enough to justify the risks. Devi, who previously worked at a hospital for a meager salary, learned to drive just so she could start working for Uber, and began driving for the platform in 2019. A single mother, she had to find work to support her two children. “That time, many women around me told me that Uber is a good option and the earnings are good,” she says. “They did not even deduct high commissions back then.”

The first time she complained to Uber was in 2020, when a customer verbally attacked her. “He was hurling abuses at me. I had complained against the customer then, but Uber didn’t do anything about it,” said Devi. “Uber never does anything when a driver complains. But even a small complaint against a driver means that they will block their account.”

At the time, she remembers spending 500 rupees ($6.08) on fuel each day but taking home 2,000 rupees ($24.39) in earnings. But lately she says the fuel costs have gone up to 700 rupees a day, while her earnings have fallen to less than 1,000 rupees.

Devi is upset that despite the life-threatening incident she experienced, the only calls she’s received from Uber are about when she will resume driving again, because she has been offline since January. She says, fuming, she has blocked those numbers. “I am worried about my children—what if something like this happens again? So I need to think really hard before taking the next steps,” she says. “For now I don’t intend to go back to driving for Uber.”

(Reporting for this story was supported by the Pulitzer Center’s AI Accountability Network.)

by crissly | Apr 11, 2023 | Uncategorized

Berlusconi was reelected as prime minister in 2008 and revived the project, which was once again approved three years later—though the price had risen from €6.16 billion ($6.72 billion) to €8.5 billion. But shortly after, amid the backdrop of an acute debt crisis in the Euro zone, Berlusconi lost his majority and resigned. His successor, Mario Monti, a respected technocrat, canceled the project a final time in 2013.

Now, the same project has been resurrected by the current government, which in mid-March approved a decree paving the way for the construction of the bridge. This time it’s championed by Matteo Salvini, deputy PM and leader of the populist League party—with support from Berlusconi, now 86, who wrote, “They won’t stop us this time” in an Instagram post on the day the decree was signed.

One of the reasons the project keeps getting revived is that there are so many people profiting from the work of planning for it, according to Nicola Chielotti, a lecturer in diplomacy and international governance at the Loughborough University in London: “They constantly spend money on it, even if it never materializes, and there are some interest groups who are happy to capture that money.”

Salvini himself has acknowledged that “it’s less expensive to build the bridge than to not build it.”

Another issue, Chielotti adds, is that the project is a useful political pawn for a government that has so far been quiet on some key electoral promises, such as tax reform and an aggressive stance towards international finance.

But the project’s strong politicization—which has resulted mainly in support from the right and opposition from the left—might also be a case of “infrastructure populism,” according to Angelini. “The rhetoric around the bridge is oozing nationalism,” he says, “and the idea is seen as a symbol of Italy’s grandeur, or the ability to build a bridge longer than anyone ever has.”

The current design for the crossing is a single-span suspension bridge with a length of 3,300 meters. That’s 60 percent longer than the Canakkale Bridge in Turkey, currently the world’s longest suspension bridge, which spans 2,023 meters. With pylons towering in at 380 meters (1,250 feet), the Messina Strait bridge would also be the world’s tallest by structural height, edging out the Millau Viaduct in France, which is 342 meters tall. It would be able to carry 6,000 road vehicles per hour and 200 trains per day, and since the span would be 65 meters above the water, naval traffic would be able to pass undisturbed beneath it.

Travel time by train between the island and the mainland—currently around two hours including the ferry journey–would be cut to under 10 minutes, bringing the nearly 5 million people who live on Sicily much closer to the rest of Italy.

Previous plans were for three spans, Muscolino says, with two pylons built in the sea, each sunk between 80 and 100 meters below sea level. These would have been unworkable, given the strong currents in the strait, and would have created a risk to shipping.